The waiting is over, the official launch date is tomorrow, and all my ducks are in a row. Well, I have no ducks, so I’ve neatly arranged my stationery just so, instead.

I have little to add to my status from the last post. I did finish with all of Block 1 before the start date, our tutor forums have opened, and nearly all communications with fellow students outside the Facebook group has stopped! I hadn’t really expected that last one, so it’s just lucky that I jumped into the FB group, even though I’ve stopped using FB apart from that. The Early Bird Café forum was always going to close before the module started, but I’d assumed that student chatter would migrate over to the students association forum for TU100, instead. Apparently it’s a bit tough for some to find. (That site makes my kitchen junk drawer look like a hospital.)

I’ve used that forum to revive another student’s great idea. (I don’t want to post the student’s name, as I haven’t checked if it should be broadcast all over the internet for no good reason.) The idea was to have some programming challenges in Sense. Someone runs into a problem while writing code, finds a creative solution for it, then challenges other students to see what solutions they can come up with to satisfy the same problem. Students who get stuck can then check the challenger’s code to see what they did.

The original challenge involved adding SenseBoard functionality to a number guessing game, which was awesome. (A SenseBoard is an Arduino-based input/ouput device for Sense. They’ve stopped selling them, but the Digital Sandbox for Scratch is the closest I’ve found for it.)

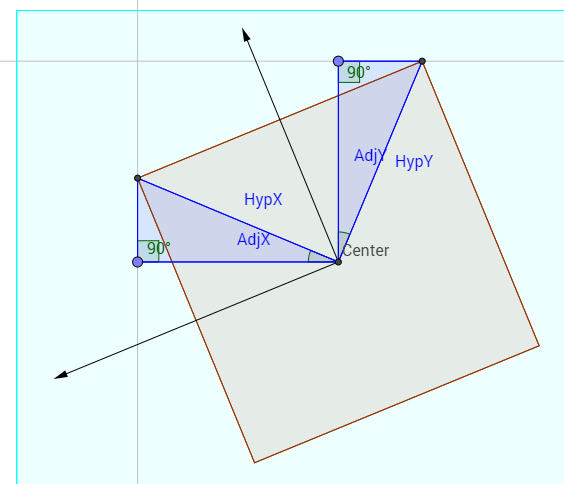

My first challenge involved making a custom score counter of arbitrary digits, which was probably the most difficult part of my Jet Bike Steve game. In Scratch, I used cloned sprites and a lot of modal maths for the digits. Sense doesn’t allow this solution, so I have to stamp the digits, instead. My initial solution used the maths from my Scratch solution, held individual digits in a list, and then stamped the list.

Within one or two hours, somebody had completely bested my design by using string slicing, which I didn’t even know was available in Sense or Scratch! How did I not know that!? (Because I hadn’t finished reading the programming guide, I later discovered.) But once he mentioned he did it without maths, I realised I could split my score digits into a list without any maths. This next revision of the challenge solution was much more optimised than my first, but still not as slick as string slicing. But the student who used it is already on his final year of the degree (and probably read the guide at some point), so I don’t feel too bad at being shown up, and I learned two great techniques thanks to him. And that’s the idea of the challenges.

One reason I felt this was necessary was the dismal state of the Sense Programming Guide that comes with the TU100 materials. And ‘dismal’ may be generous. In fact, the fiery hellish abyss of computational programming pedagogy might be generous.

It’s not actually bad, I suppose, as it isn’t wrong. It just doesn’t fit the brief. According to a paper presented at a symposium detailing the reasons for TU100 and Sense’s existance (Richards et al, 2012, p. 584), one of the main failings of previous OU introductory programming modules was failure to engage students with experimentation.

What they’ve done is assembled a great tool box in Sense and the SenseBoard, and then forgot to actually encourage experimentation, or put another way, to teach the students how to experiment.

Much of the Programming Guide is direct instructions of which buttons to push. When it comes for explorative activities, the exercises are only open so far as to find the “correct” answer to a limited scenario. There are no open-ended exercises of any kind in the guide. It actively discourages experimentation.

It does, however, go over string slicing, so I didn’t have to discover that on my own. It was more fun, engaging, and easily remembered that way, though.